Coastal engineers practice what they preach, using a variety of techniques to maintain beaches as a first line of defence against tropical storms and storm surge. While there’s no argument that sand dunes provide key protection, new research highlights the importance of size, shape, and strategy in maintaining a beach’s nearshore and dunes. The study explores erosion as a function of what’s known as the dune aspect ratio, the measure of a dune’s height to its width. It was published in September 2021 in the journal Earth Surface Dynamics and provides additional metrics for engineers and coastal management planners to engage in their work.

The key finding, and not surprisingly, is that “…a wide beach offers the greatest protection from erosion in all circumstances.” But the research also found that wider, lower dunes protected better against longer, more moderate storms, while taller, thinner dunes better prevented overtopping during quicker, more intense storms.

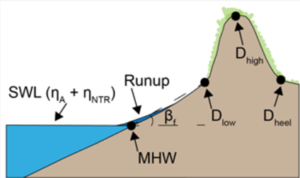

D= dune (toe, heel, crest), MHW = mean height of water. SWL= still water level. B= beach slope.

Source: “The Relative Influence of Dune Aspect Ratio and Beach Width and Dune Erosion as a Function of Storm Duration and Surge Level” (2021) Itzkin, M., Moore, L, Ruggiero, P., Hacker, S., and Biel, L. (modified from Sallenger 2000).

The team, from universities on opposite coasts of the United States, used a popular open-source program called XBeach, which models wave propagation, sediment transport and morphological changes of the nearshore, beaches, dunes, and backshore during storms. Smith Warner International Coastal Engineer Miles Harris, who works with XBeach, but was not involved in this particular study, explains, “XBeach gives the flexibility to build a model up using the core principles of physics. Therefore, we can represent the unique and complex shorelines of the Caribbean by replicating the known natural processes in the XBeach domain.”

Maintaining a wide beach, whether naturally or with the assistance of beach nourishment or sand fencing, often involves decreasing its slope to allow wave energy to dissipate. While wind and gravity play a role, “Wave action is the driving force for beach movement,” Miles continues. “The larger the wave offshore the more damage it creates in the nearshore…In a storm, the wave level rises

and it’s harder for the wave to ‘feel’ the seabed. As a result, larger waves go inland.” Sometimes, even after a wave breaks, so much energy remains that it can reach the dune system.

The Complexity of the Dune System

In building and maintaining a strong dune system, sand fencing has proven highly effective in trapping sand and allowing the dunes behind the fencing to grow. This growth often comes more in terms of width than in height, giving the dunes more room to erode during a long storm before the system is breached.

Sand dune fencing in Anguilla during a 1998 OECS pilot study

However, the dune system is complex, as many of the same researchers illustrated in an earlier study published in 2020 in the journal Geomorphology. That study found that while sand fencing promoted lower and wider “foredunes” by encouraging the accumulation of sand, it may not always be the best practice because, “… sand fences block sediment supply to landward dunes, leading to a shorter and wider complex foredune than would otherwise naturally occur.” And if the fencing process is not paired with beach nourishment (which the researchers do not promote in their study), the result could be “a slightly narrower beach.” Their concern is then that, “The lower aspect ratio could serve to reduce erosion, but this potential decrease in erosion may well be offset by increased erosion associated with the narrower beach.”

“Overwash” that occurs when waves top the sand dunes is an important natural process. For barrier islands, it carries sediment to the back of the island which, over time, naturally allows the island to maintain its height and keep pace with rising sea levels. Tall, thin dunes can block overtopping and deprive the barrier island of sediments. So the management of that type of dune system must balance natural coastal processes with the protection of residences and infrastructure that have been built close to the sea.