You’ve seen them all over the world: coastal structures made of layers of large rocks (known as rock armour), designed to resist wave action and protect the shoreline behind it. What you may not have seen is that, especially in the Caribbean, these structures can transform the underwater landscape from a barren substrate into a diverse marine ecosystem providing valuable ecosystem services.

We looked at several locations across the Caribbean over years and even decades to see what had changed during the time since the structures were first built. We looked at the ecosystem services provided by coral reefs and what other researchers found in determining their value and contribution to national economies. Finally, using the estimated transition from barren substrate to thriving coral community, we calculated the value of the ecosystem services provided by rock armour.

We looked at rock armour structures in three countries across the Caribbean. All of these structures were built using rock from local quarries. The first is in St Lucia. Six months after construction was completed, there was a lot of green fleshy algae (below left) forming on the boulders but one year later (below right) different species of algae were more prevalent.

To see longer-term changes in this transition from rock armour to ecosystem, we studied two different locations in Jamaica.

In Negril we looked at two groynes that were built to stabilize newly created beaches for hotels. We had been monitoring them since they were built and what we saw was that even just two years post-construction, small (fingernail sized) coral recruits were already colonizing the boulders (left).

We also looked at structures around Montego Bay including both the submerged and emergent portions of an offshore breakwater. What we found was that both the outer areas (i.e., exposed to wave action) and submerged sills had very little coral coverage, while the interior sheltered portions supported the highest coral cover. These structures were monitored 6 years after construction. Here we are seeing different species of corals, different size ranges, and considerable numbers of fish. Finger corals on the left and brain coral on the right (photos below).

The last site in Jamaica was in Montego Bay. The structure is a submerged sill that holds the beach sand in place and sits just offshore a major public beach creation project that was completed about 45 years ago. On this structure we observed large coral specimens 70cm and greater, and more than 10 different species (three photos below).

Finally, we looked a complex ecosystem with large and varied coral, fish and other marine organisms in Barbados. This submerged breakwater on the south coast was built in the early 1990’s as part of major coastal management study undertaken by the Government.

The photo on the left was taken in 1993, about 6 months after 15,000 tonnes of bright white boulders were placed. Our founding partners, David Smith and Philip Warner, were quite excited about all the fish at the time. The photo on the right is the same breakwater 25 years later: more than 10 different coral species, and too many individuals to count; 25 different species of fish, with thousands of individuals; soft and hard corals, sponges, juvenile and adult fish, and Hawksbill Turtle.

Instead of one species of fish nibbling on the algae, there is a complex ecosystem consisting of many different species of corals, fish, algae, gorgonians and sponges. Among the different fish species, there were predators and prey, juveniles and adults, large and small, implying that a complex ecosystem had become established on this structure. This area has been declared as a marine reserve, so no fishing is allowed.

Based on these results and comparing them to nearby natural reef areas in Montego Bay and Barbados, we estimated that within 2 years rock armour progresses from a barren substrate to a something that supports fish and is colonizing small corals. Within 5 -7 years rock armour is supporting several different coral species and at 20 years rock armour can achieve 90% of the function of nearby coral reefs.

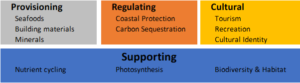

To see if this transition was providing benefits we looked at the concept of ecosystem services. In the early 2000’s the Secretary General of the UN commissioned the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. This looked at all ecosystem services (services that nature provides that we can benefit from). Essentially, there are supporting services that are indirect, and three main direct services including provisioning, regulating and cultural. For marine ecosystems, this has been further refined, or focused.

Mark Spalding from The Nature Conservancy estimated in a 2017 study that reef tourism is worth USD 35.8 billion per year. In the Turks and Caicos Islands and the British Virgin Islands, coral reefs support over one third of all tourism value and 10% or more of the entire GDP. In a 2018 paper, Michael Beck et al estimated that annual coastal damage is reduced by USD 4 billion across reef coastlines.

From our studies:

- Transformation takes time ~15-20yrs

- Rock armour becomes a thriving ecosystem that is similar to adjacent coral reefs

- Valuable ecosystem services beyond shoreline protection are provided

- Variation in reef value across Caribbean is large

- Distinction between grey and green is not always clear-cut

By providing some measured values of the ecosystem services that rock armour provides once it makes the transition from rocks to coral reef, we have shown that the traditional distinction between engineering structures – which are often considered grey – and green, nature-based solutions is not always clear-cut. In the Caribbean Sea, and presumably elsewhere, engineering and natural ecosystems can work in tandem to provide solutions.