This is a story of regeneration and of nature’s power to rebuild and restore with some analysis and help from mankind. In a way, this article is written backward with the happy ending first. Now, the story of what went wrong and what turned the tide.

Why a developer was granted permission to embark on a large marina, condo, and golf course project in a national conservation area is a thing of the past. But that is exactly what happened in the early 1990’s in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. The “Ashton Marina Project” was slated to house a marina with 300 berths, a large condominium complex, and a 50-acre golf course that stretched over a mangrove forest. A marina causeway would connect Frigate Island to Union Island. Work began in 1994 on the causeway with the installation of metal pilings and berths in Ashton Lagoon.

The following year the investor went bankrupt and work on the project stopped. But enormous damage to the site’s mangroves, reefs, and seagrass had already occurred. Dredging and the construction of the causeway across the lagoon had impeded water circulation. The water was polluted and the buildup of sediments deprived the marine ecosystem of oxygen. The mangroves, corals, and seagrasses were dying.

The following year the investor went bankrupt and work on the project stopped. But enormous damage to the site’s mangroves, reefs, and seagrass had already occurred. Dredging and the construction of the causeway across the lagoon had impeded water circulation. The water was polluted and the buildup of sediments deprived the marine ecosystem of oxygen. The mangroves, corals, and seagrasses were dying.

More than 20 years later, Sustainable Grenadines (SusGren) led a multinational group of conservationists and donors in a mission to restore the area’s ecosystems’ health and biodiversity. The group (The Nature Conservancy, BirdsCaribbean, Union Island Environmental Attackers, St. Vincent and the Grenadines National Parks, Rivers and Beaches Authority, St. Vincent and the Grenadines Ministry of Agriculture) hired Smith Warner International to explore remediation alternatives and to provide a detailed design, budget, and construction methodology for the preferred solution.

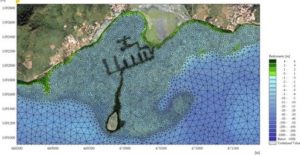

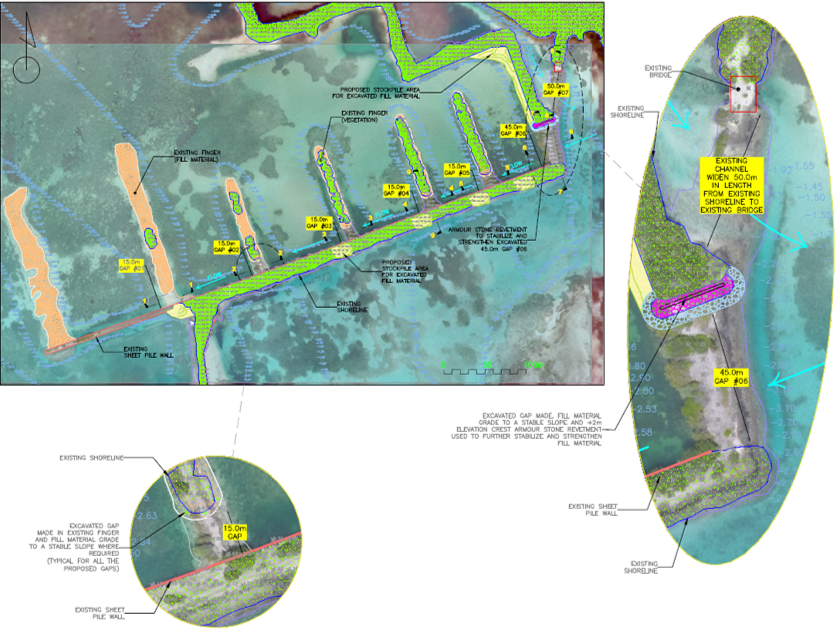

“A big part of our role in the restoration was to optimize the process of dismantling the failed marina so that water circulation could be improved,” explains Smith Warner co-founder and Director of Operations Philip Warner. “Removing all of the causeway and structures would have cost millions and once again put stress on the environment through disturbance and stirring up of silt.” He continues, “Using numerical modeling simulations, we identified the key areas of the causeway that needed to be removed. This restored the water circulation and eliminated the stagnation that was leading to algal blooms and dead zones (areas deprived of oxygen).”

“A big part of our role in the restoration was to optimize the process of dismantling the failed marina so that water circulation could be improved,” explains Smith Warner co-founder and Director of Operations Philip Warner. “Removing all of the causeway and structures would have cost millions and once again put stress on the environment through disturbance and stirring up of silt.” He continues, “Using numerical modeling simulations, we identified the key areas of the causeway that needed to be removed. This restored the water circulation and eliminated the stagnation that was leading to algal blooms and dead zones (areas deprived of oxygen).”

Smith Warner engineers designed a system to reconnect the mangroves with the sea, restoring flow to the inner lagoon and increasing flushing of much-needed water to maintain an important habitat for birds, fish, and other marine organisms.

Over the course of the restoration project 3,000 mangroves were planted. Conservation groups developed awareness programs to educate residents and tourists about biodiversity and climate change and to engage them in community cleanup. Training of local tour guides enabled new ecotourism activities. BirdsCaribbean still provides support for clean-up activities, tree planting and signs for the bird towers.

In addition to remediation of the ecological damage from the marina development, Sustainable Grenadines considers the Ashton Lagoon Restoration Project to be a pilot for using ecosystem-based adaptation to build coastal resilience and reduce the risk of damage from natural disasters. The economy of St Vincent and the Grenadines relies strongly on the coast and marine environment. The islets and cays are highly vulnerable to sea level rise, storm surge, and flooding. Mangroves, corals, and seagrasses all provide important layers of defense. Community Field Researchers from SusGren now monitor the area regularly to gauge how the ecosystem is responding to the improvements and to track water quality and marine health.

In addition to remediation of the ecological damage from the marina development, Sustainable Grenadines considers the Ashton Lagoon Restoration Project to be a pilot for using ecosystem-based adaptation to build coastal resilience and reduce the risk of damage from natural disasters. The economy of St Vincent and the Grenadines relies strongly on the coast and marine environment. The islets and cays are highly vulnerable to sea level rise, storm surge, and flooding. Mangroves, corals, and seagrasses all provide important layers of defense. Community Field Researchers from SusGren now monitor the area regularly to gauge how the ecosystem is responding to the improvements and to track water quality and marine health.